TL;DR

- Transformers replace RNNs/CNNs with pure attention mechanisms for sequence modeling

- Self-attention allows parallel processing and captures long-range dependencies

- Multi-head attention enables learning different types of relationships simultaneously

- Foundation for all modern language models (BERT, GPT, T5, etc.)

The Paper That Changed Everything

Some papers slip quietly into your workflow; this one kicked the door in. Attention is All You Need (Vaswani et al., 2017) didn’t iterate; it replaced an era. It rewrote how we think about sequence modeling, not by adding yet another clever recurrence, but by walking away from recurrence entirely.

The Transformer became the substrate for almost everything that followed: BERT, GPT, T5 - and then it jumped fences into vision, speech, and multimodal systems.

Why We Needed Something Better

Before Transformers, we were stuck with RNNs and CNNs for sequence modeling, and honestly, they were frustrating to work with. I remember spending hours waiting for models to train, dealing with vanishing gradients, and constantly hitting the limits of what these architectures could do.

The problems were everywhere: RNNs had to process sequences one step at a time, which meant training was painfully slow. Try to learn long-range dependencies? Good luck with those vanishing gradients. Want to parallelize training? Forget it - the sequential nature made that impossible.

The Transformer's breakthrough was realizing we didn't need recurrence or convolution at all. Instead of processing sequences step-by-step, what if we could look at all positions simultaneously and let the model figure out which parts are important? That's exactly what attention mechanisms do - and it changed everything.

The Heart of the Matter: Self-Attention

Self-attention is like giving the model the ability to look at every word in a sentence simultaneously and decide which ones are most important for understanding any given word. It's like having a conversation where you can instantly reference anything that was said earlier, without having to remember it step by step.

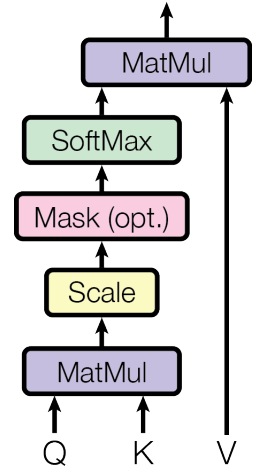

For each word in the sequence, the model creates three vectors: a Query - $\mathbf{Q}$ (what am I looking for?), a Key - $\mathbf{K}$ (what do I represent?), and a Value - $\mathbf{V}$ (what information do I contain?). Then it computes how much attention each word should pay to every other word:

\[ \text{Attention}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\mathbf{V} \]The \(\sqrt{d_k}\) scaling factor is a neat trick that prevents the attention scores from becoming too extreme when the dimensions get large. Without it, the softmax would become too peaked, and the model would essentially ignore most of the input. It's one of those small details that makes a big difference.

But... what exactly are the $\mathbf{Q}$, $\mathbf{K}$, and $\mathbf{V}$ vectors? They are simply linear transformations of the input embeddings:

\[ \mathbf{Q} = \mathbf{W}^Q \mathbf{x} \] \[ \mathbf{K} = \mathbf{W}^K \mathbf{x} \] \[ \mathbf{V} = \mathbf{W}^V \mathbf{x} \]where $\mathbf{W}^Q$, $\mathbf{W}^K$, and $\mathbf{W}^V$ are the weight matrices for the query, key, and value projections; $\mathbf{x}$ is the input embedding.

Question: What are the shapes of $\mathbf{Q}$, $\mathbf{K}$, and $\mathbf{V}$?

Answer: $\mathbf{Q}$ is of shape $(n, d_k)$, $\mathbf{K}$ is of shape $(n, d_k)$, and $\mathbf{V}$ is of shape $(n, d_v)$, where $n$ is the number of tokens in the sequence, $d_k$ is the dimension of the key, and $d_v$ is the dimension of the value.

Why One Head Isn't Enough

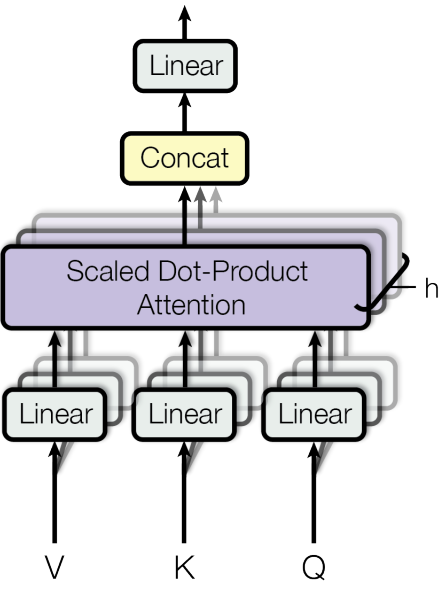

Instead of just one attention mechanism, Transformers use multiple "heads" running in parallel. It's like having several people read the same text simultaneously, each looking for different patterns.

One head might focus on grammatical relationships (like which verb goes with which subject), while another might pay attention to semantic connections (like which words are related in meaning). A third might look for positional relationships (like which words are close together). By combining all these different perspectives, the model gets a much richer understanding of the text.

\[ \text{MultiHead}(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}) = \text{Concat}(\text{head}_1, \ldots, \text{head}_h)\mathbf{W}^O \]Each head learns its own set of attention patterns, and then they all get combined at the end. It's like having a team of experts, each with their own specialty, all working together to understand the same input.

Putting It All Together

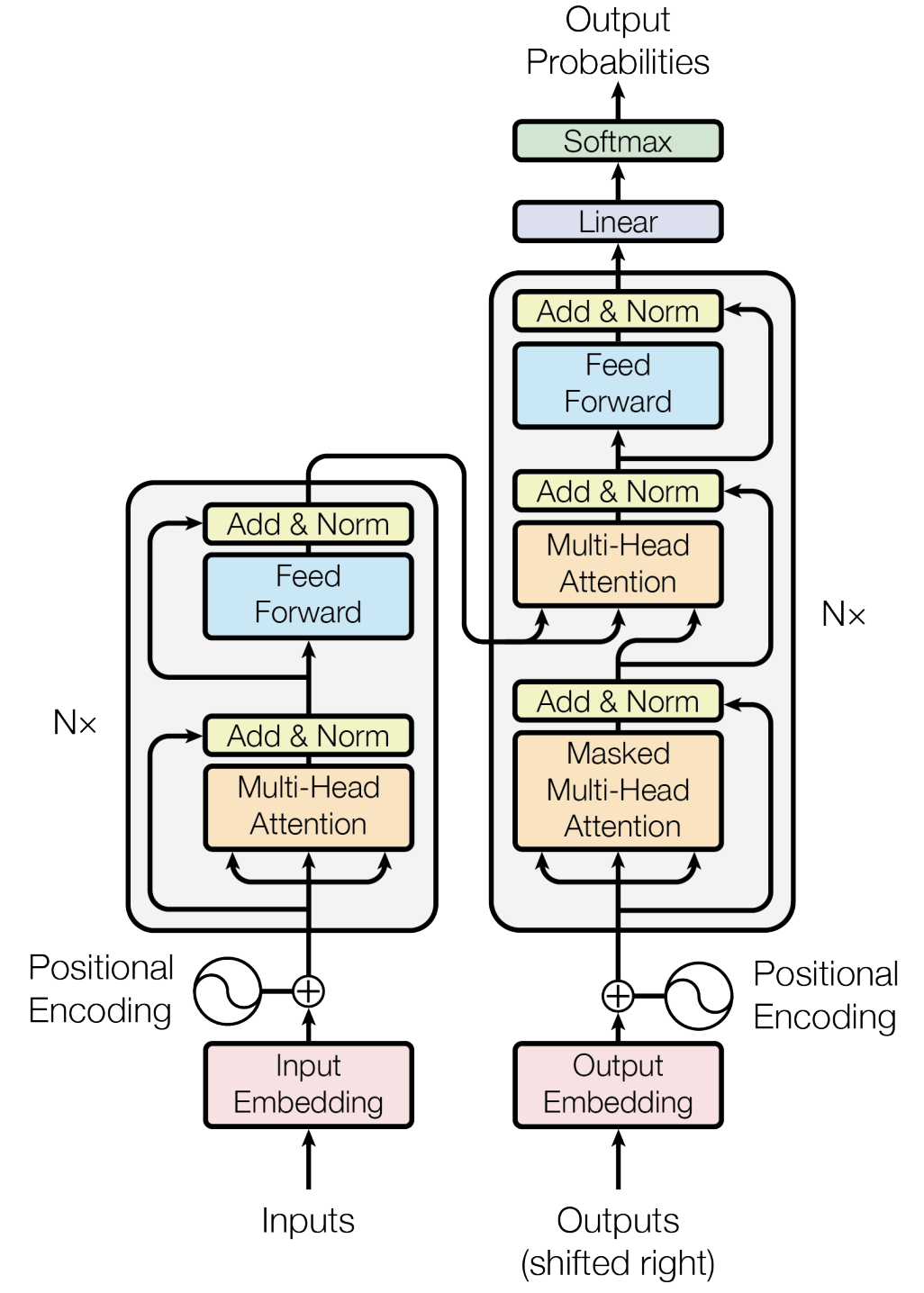

Now we get to see how all these pieces fit together. The Transformer uses an encoder-decoder architecture, but it's not like the old RNN-based ones. Both the encoder and decoder are built from the same basic building blocks: attention mechanisms, feed-forward networks, and residual connections.

The encoder takes your input sequence and creates rich representations that capture all the relationships between words. The decoder then uses these representations to generate the output, but here's the clever part: it can attend to the entire input sequence at once, not just the previous words. This is what makes translation and other sequence-to-sequence tasks so much more effective.

Encoder Layer

Each encoder layer consists of:

\[ \mathbf{x} = \text{LayerNorm}(\mathbf{x} + \text{MultiHeadAttention}(\mathbf{x})) \] \[ \mathbf{x} = \text{LayerNorm}(\mathbf{x} + \text{FFN}(\mathbf{x})) \]Where FFN is a position-wise feed-forward network: \(\text{FFN}(x) = \max(0, xW_1 + b_1)W_2 + b_2\)

Decoder Layer

Each decoder layer has three sub-layers:

- Masked self-attention: Prevents attending to future positions

- Encoder-decoder attention: Attends to encoder outputs

- Position-wise FFN: Same as encoder

The Position Problem

Initially, this confused me about Transformers: they don't naturally understand word order. Unlike RNNs that process words sequentially, Transformers look at all words at once, so "the cat sat on the mat" and "the mat sat on the cat" would look identical to them.

The solution that was proposed in the paper was to add some special numbers to each word that encode its position in the sequence. These positional encodings use sine and cosine functions with different frequencies:

\[ PE_{(pos, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{model}}}\right) \] \[ PE_{(pos, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{model}}}\right) \]The beauty of this approach is that it can handle sequences of any length, and the model can learn to understand relative positions (like "the word 3 positions before this one"). This gives each word a unique address that tells the model where it belongs in the sequence.

The Training Recipe

Getting Transformers to train well required some careful tuning. The authors used several techniques that have since become standard practice:

- Optimizer: Adam with \(\beta_1 = 0.9\), \(\beta_2 = 0.98\), \(\epsilon = 10^{-9}\)

- Learning rate: \(lrate = d_{model}^{-0.5} \cdot \min(step\_num^{-0.5}, step\_num \cdot warmup\_steps^{-1.5})\)

- Regularization: Dropout (\(p = 0.1\)) and label smoothing (\(\epsilon_{ls} = 0.1\))

- Batch size: $25,000$ tokens per batch

The Results

When the results came in, they were impossible to ignore. The Transformer didn't just beat the previous state-of-the-art – it crushed it, and it did so while training much faster than anything that came before.

On the standard machine translation benchmarks, the improvements were dramatic: 28.4 BLEU on English-German (up from 25.16) and 41.8 BLEU on English-French (up from 40.46). But what really caught my attention was the training time: just 3.5 days on 8 GPUs, compared to weeks for the previous best RNN-based models.

This wasn't just about better performance – it was about making the impossible possible. Suddenly, you could train large language models in days instead of weeks. You could experiment with different architectures without waiting months for results. The Transformer didn't just improve the state of the art; it democratized it.

Machine Translation Results

| Model | WMT $2014$ EN-DE BLEU | WMT $2014$ EN-FR BLEU | Training Time | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer (base) | $28.4$ | $41.8$ | $12$ hours | $65M$ |

| Transformer (big) | $28.9$ | $41.4$ | $3.5$ days | $213M$ |

| ConvS2S | $25.16$ | $40.46$ | $9$ days | $38M$ |

| ByteNet | $23.75$ | $-$ | $-$ | $-$ |

| GNMT | $24.6$ | $39.92$ | $-$ | $-$ |

Model Variants and Ablations

| Model Variant | EN-DE BLEU | Parameters | Training Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer ($6$ layers) | $28.4$ | $65M$ | $12$ hours |

| Transformer ($2$ layers) | $27.3$ | $37M$ | $6$ hours |

| Transformer ($1$ layer) | $26.5$ | $28M$ | $3$ hours |

| Single-head attention | $27.3$ | $65M$ | $12$ hours |

| No positional encoding | $26.8$ | $65M$ | $12$ hours |

Computational Complexity Comparison

| Layer Type | Complexity per Layer | Sequential Operations | Maximum Path Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Attention | $O(n^2d)$ | $O(1)$ | $O(1)$ |

| Recurrent | $O(nd^2)$ | $O(n)$ | $O(n)$ |

| Convolutional | $O(knd^2)$ | $O(1)$ | $O(\log_k(n))$ |

| Self-Attention (restricted) | $O(rn^2d)$ | $O(1)$ | $O(n/r)$ |

What Made Transformers So Powerful

The advantages of Transformers go beyond just better performance. They fundamentally changed how we think about sequence modeling:

- Parallelization: Unlike RNNs that had to process sequences step-by-step, Transformers can look at all positions simultaneously. This made training much faster and more efficient.

- Long-range dependencies: Any two words in a sequence can directly interact, no matter how far apart they are. This solved the vanishing gradient problem that plagued RNNs.

- Interpretability: The attention weights actually tell us what the model is focusing on, which is incredibly useful for understanding and debugging.

- Flexibility: Transformers naturally handle sequences of any length without architectural changes, making them much more versatile than their predecessors.

- Efficiency: For long sequences, Transformers are significantly faster to train than RNNs, even though the attention mechanism has quadratic complexity.

The Trade-offs We Had to Accept

As powerful as Transformers are, they come with their own set of challenges that researchers are still working to solve:

- Quadratic complexity: The attention mechanism scales as $O(n^2)$ with sequence length, which becomes a real bottleneck for very long sequences. This is why we're seeing so much research into more efficient attention variants.

- Memory requirements: Storing attention matrices for long sequences can quickly consume all available GPU memory. I've run into this limitation more times than I'd like to admit.

- Position encoding: The fixed sinusoidal positional encodings work well for training lengths, but they don't always generalize to much longer sequences during inference.

- Inductive bias: Unlike RNNs and CNNs, Transformers have less built-in structure, which means they need more data to learn effectively. This is both a strength and a weakness.

- Training instability: Getting the hyperparameters just right can be tricky, and small changes can sometimes lead to training failures. It's one of those things that gets easier with experience.

The Era of Transformers

Looking back, it's hard to overstate how much the Transformer changed the field. What started as a machine translation paper became the foundation for an entire generation of AI systems:

- Foundation for modern LLMs: BERT, GPT, T5, PaLM, ChatGPT, etc.

- Beyond NLP: Vision Transformers, speech processing, multimodal models

- Research acceleration: Enabled rapid progress in AI

- Industry adoption: Used in virtually all production language systems

- New paradigms: Prompting, in-context learning, instruction following

Citation

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., et al. "Attention is All You Need." NeurIPS 2017. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762.