TL;DR

- CLIP trains image and text encoders jointly using contrastive learning

- Enables zero-shot classification by comparing images to text prompts

- Learns rich visual representations from natural language supervision

- Foundation for many multimodal models and zero-shot vision applications

The Big Picture

Open your photo library and try describing a picture out loud: "a sleepy orange cat on a sunlit windowsill". That's closer to how we think than a rigid label like "cat" or "dog". CLIP (Radford et al., 2021) leans into that simple truth. Instead of memorizing category lists, it learns the language of images - the messy, specific, wonderfully human way we talk about what we see.

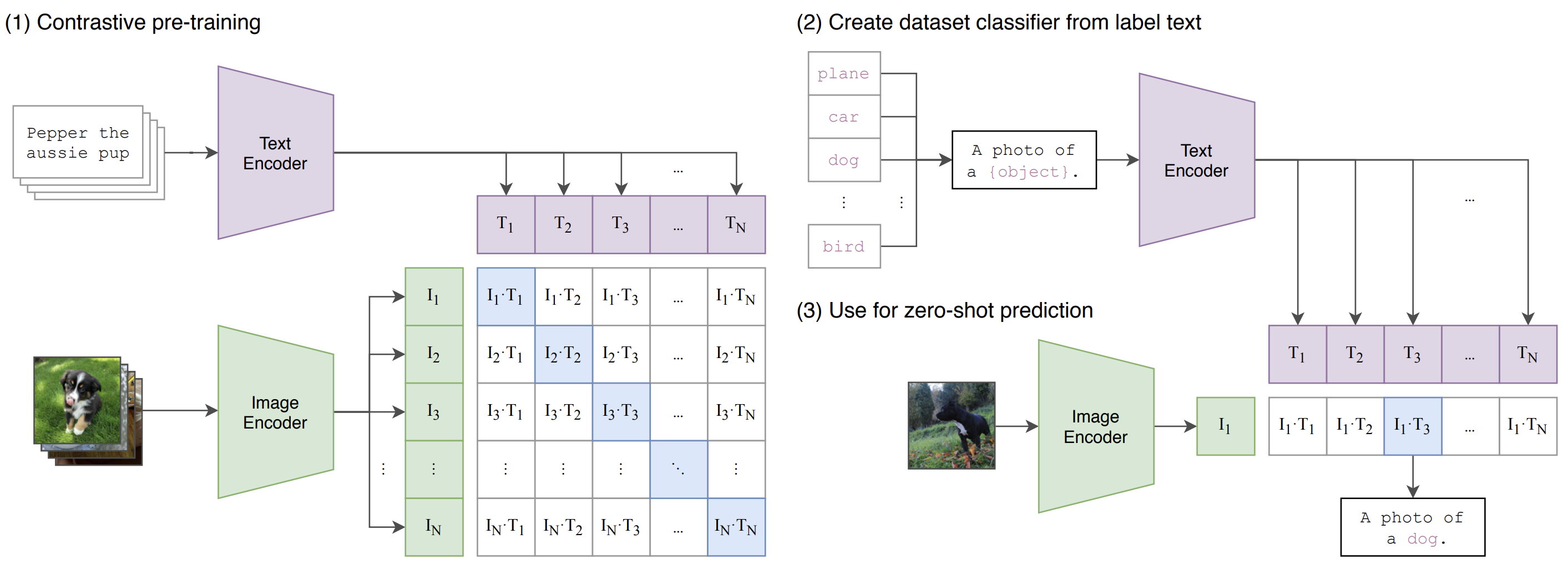

Under the hood, the idea is disarmingly direct: learn two encoders - one for images, one for text - and pull matching pairs together in a shared space while pushing everything else apart. Once that space exists, zero-shot classification becomes a conversation: describe what you want in natural language, compare it to the image, and pick what fits. No task-specific retraining. No bespoke datasets. Just words and pictures meeting in the middle.

How CLIP Actually Learns

The magic happens through something called contrastive learning. Think of it like teaching a child to match pictures with descriptions. You show them a photo of a cat with the text "a cat sitting on a chair," and you want them to learn that this image and this text go together. But you also show them the same image with descriptions of other things like "a dog running" or "a car parked outside," and they learn that these don't match.

Mathematically, CLIP does this with a symmetric contrastive loss. For a batch of \(N\) image-text pairs, it computes similarities between all possible combinations and tries to maximize the similarity between matching pairs while minimizing everything else. The beauty is in the symmetry – it learns both directions: given an image, find the right text, and given text, find the right image.

\[ \mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2}\Bigg( \underbrace{\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \! -\log \frac{\exp(s_{ii})}{\sum_{j=1}^{N} \exp(s_{ij})}}_{\text{image} \to \text{text}} \; + \; \underbrace{\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \! -\log \frac{\exp(s_{ii})}{\sum_{j=1}^{N} \exp(s_{ji})}}_{\text{text} \to \text{image}} \Bigg). \]This symmetric approach is what makes CLIP so robust. It's not just learning to recognize images – it's learning a true understanding of the relationship between visual and textual concepts. When I first saw this, I realized it was solving a much deeper problem than just image classification.

The Two-Encoder Setup

CLIP's architecture is refreshingly straightforward – no fancy tricks, just two encoders doing their job. The image encoder (usually a ResNet or Vision Transformer) takes in images and spits out embeddings. The text encoder (a Transformer) does the same for text. Both outputs get projected into the same shared space where the magic happens.

What I find elegant about this design is how it mirrors how we actually process information. When you see a sunset, your visual cortex processes the image while your language centers can simultaneously generate a description. CLIP essentially replicates this dual processing in a neural network.

The Scale That Made It Work

Here's where things get interesting. CLIP was trained on a staggering $400$ million image-text pairs scraped from the web. That's not just a lot of data - it's a completely different kind of data than what we'd been using before. Instead of carefully curated datasets with perfect labels, CLIP learned from the messy, noisy, but incredibly diverse world of internet images and their captions.

I remember thinking when this paper came out: "Of course it works - they're using the entire internet as their training set!". But that's actually the genius of it. By training on such diverse, real-world data, CLIP learned to understand concepts that would never appear in traditional datasets. It learned about memes, artistic styles, cultural references, and all the weird, wonderful ways humans actually describe what they see.

The Magic of Zero-Shot Learning

Once you have your trained model, you can classify images into completely new categories without any additional training. Want to find images of "a dog wearing sunglasses" or "a person riding a unicycle"? Just describe it in natural language, and CLIP will find it.

The process is beautifully simple: you create text prompts describing what you're looking for (like "a photo of a cat" or "a person playing guitar"), encode both the image and the text prompts, then find which text embedding is most similar to the image. The math is just cosine similarity:

\[ \hat{k} = \arg\max_k \; \frac{\langle v, t_k \rangle}{\lVert v \rVert \, \lVert t_k \rVert}. \]What's remarkable is how well this works. I've used CLIP to search for things like "a person doing yoga on a beach at sunset" and it actually finds relevant images. It's like having a conversation with your computer about what you want to see, and it understands you perfectly.

What Blew My Mind

The results were genuinely surprising. CLIP achieved zero-shot performance that was competitive with models that had been specifically trained on those datasets. But what really got me excited were the things that traditional models couldn't do at all.

- Broad transfer: The same model that learned from internet images could suddenly classify medical X-rays, satellite imagery, or artistic paintings without any additional training. It was like watching someone who learned English from reading novels suddenly become fluent in poetry, technical manuals, and street slang.

- Compositionality: You could ask for things that had never been explicitly trained on. "A red car in the rain" or "a person reading a book while standing on one leg" - CLIP understood these complex, compositional concepts because it had learned the building blocks of visual understanding.

- Retrieval: The bidirectional nature meant you could go both ways - find images that match text descriptions, or find text descriptions that match images.

The Numbers That Matter

While the qualitative improvements were impressive, the quantitative results really drove home how significant CLIP's breakthrough was. For complete details, the original paper has all the numbers: arXiv:2103.00020.

Zero-shot Image Classification

| Backbone | Setting | Dataset(s) | Outcome Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet / ViT variants | Zero-shot | ImageNet (and variants) | Competitive with a supervised ResNet-50 without using ImageNet labels; strong transfer via prompts. |

| ResNet / ViT variants | Zero-shot | 30+ datasets (e.g., CIFAR-100, OxfordPets, Flowers, Food, SUN397, Caltech101) | Consistent zero-shot gains vs. chance and competitive with supervised baselines; benefits from prompt ensembles. |

Linear Probe Transfer

| Representation | Probe | Dataset(s) | Outcome Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP image encoder | Linear classifier | ImageNet and standard transfer suites | Strong linear separability; linear probe narrows the gap to supervised training on many datasets. |

Image–Text Retrieval

| Task | Metric | Dataset(s) | Outcome Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image→Text, Text→Image | Recall@K | Common benchmarks (e.g., Flickr/Coco) | Competitive retrieval without task-specific training due to shared embedding space and symmetric loss. |

Robustness and Distribution Shift

| Evaluation | Dataset(s) | Outcome Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-shot under distribution shift | ImageNetV2, ImageNet-R, ImageNet-Sketch, etc. | Improved robustness compared to supervised ImageNet models; language priors aid generalization. |

Note: This section is a structured summary of the paper's reported results. For exact numeric scores, please refer to the tables and figures in the paper [link].

The Reality Check

As much as I love CLIP, it's not perfect. The same web data that gave it such broad understanding also brought along all the biases and quirks of human society. I've seen CLIP struggle with things that seem obvious to us – it might associate certain professions with specific genders, or have trouble with images from cultures it wasn't well exposed to during training.

- Bias and spurious cues: The web is a messy place, and CLIP learned from all of it. It's a reminder that our models are only as good as the data we feed them.

- Localization: CLIP sees the big picture but misses the details. Ask it to find "a person pointing at something" and it might find the person, but it won't tell you exactly where they're pointing. Sometimes you need that fine-grained spatial understanding.

- Domain shift: When I tried using CLIP on medical images or scientific diagrams, it often struggled. The visual language of these domains is so different from typical web images that CLIP's learned representations just didn't transfer well. It's like asking someone who learned English from social media to read a physics textbook.

And One More Thing...

There's one parameter in CLIP that often gets overlooked but can make a huge difference in practice: the temperature \(\tau\). It controls how "sharp" the similarity distributions are – lower values make the model more confident in its predictions, while higher values keep things more uncertain. I've found that tuning this carefully is crucial, especially when the batch composition changes.

\[ p_{ij}^{(I\to T)} = \frac{\exp(\langle v_i, t_j \rangle / \tau)}{\sum_{k} \exp(\langle v_i, t_k \rangle / \tau)}\,, \quad p_{ij}^{(T\to I)} = \frac{\exp(\langle t_i, v_j \rangle / \tau)}{\sum_{k} \exp(\langle t_i, v_k \rangle / \tau)}. \]Where This Led Us

CLIP didn't just solve a technical problem – it opened up a whole new way of thinking about vision and language. It showed us that you could learn powerful visual representations from natural language supervision, and that opened the floodgates for everything that came after.

Today, we have models like GPT-4V that can not only understand images and text together, but can actually reason about them, answer questions, and even generate new content. But they all trace their lineage back to CLIP's core insight: that language is the natural interface for visual understanding. It's like CLIP taught us the alphabet, and now we're writing novels.

Citation

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., et al. “Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision.” arXiv, 2021. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.00020.